by Mohammed Barber

“We are in the midst of unparalleled difficulties and untold sufferings”

Mohammed Ali Jinnah, 1947

The Second World War was a game changer for India, and though Independence became tantalisingly close in 1945, partition was a more complicated affair, but not inevitable

This article will trace the demand for Pakistan, and the violence that accompanied the birth of modern India and Pakistan

The Demand for Pakistan

The official launch of the Pakistan movement is often dated back to the 1940 Lahore Resolution. Jinnah announced that “the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority as in the North-Western and Eastern Zones of India should be grouped to constitute “Independent States” in which the Constituent Units shall be autonomous and sovereign.”

However, the Resolution made no mention of “Pakistan” or partition, and has no precise geographical definition of where these “Independent States” (note the plural States) will be located.

Moreover, crucially, as Barbara Metcalf points out “Appearances to the contrary, nothing at this point was certain, much less inevitable. Above all, it is important to avoid reading back into the 1940 Resolution the Pakistan state that emerged in 1947…until 1946 no one, neither Jinnah, the provincial Muslim leaders, nor the British, envisaged, much less desired, the partition that ultimately took place.”

It is remarkable that Jinnah announced his Resolution only three years after the 1937 elections, which saw the League take only 5% of the Muslim vote and secured few victories in the key Muslim majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal.

Jinnah immediately took to reforming the Muslim League, turning it into a political party with mass Muslim support to buttress its claim to speak on behalf of all Muslims and popularise the “two-nation” theory.

WWII was a major turning in this political revamp. As the League filled the gap Congress left after resigning from provincial government, turning Jinnah from a politician both Congress and the British wilfully side-lined, into a figure whose consent to any Independence plan could not be ignored.

It was within this context that he announced the Lahore Resolution.

In the 1945/46 elections, the Muslim League won all the Muslim seats to the central assembly, and took 75% of the total Muslim vote cast in the provincial assemblies. Jinnah’s efforts had paid off, he now had a mandate for “Pakistan”. However, as historians Ayesha Jalal and Sugata Bose point out, even at this late juncture, “No one had a clear idea about the exact meaning of ‘Pakistan’, let alone its precise geographical boundaries….Muslims had not voted for a specific agenda because no agenda had been detailed.”

Jinnah, quite deliberately, kept things vague. First, he wanted the concession for nationhood, the details could be hammered out later.

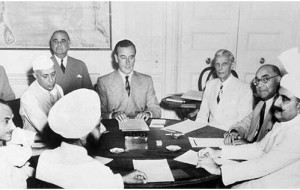

Cabinet Mission 1946

The closest Congress and the League ever came to this concession was the Cabinet Mission of 1946. This plan proposed a three tier federation: the Muslim majority provinces of North-Western Frontier, Punjab and Sindh as one group, Bengal and Assam in the east as another – these two groups would make up Pakistan – and Bombay, the Central Provinces, United Provinces and Madras as the third group.

Above all, Jinnah wanted parity for his Pakistan with Hindu India, and the compulsory grouping of semi-autonomous provinces in an Indian Union came very close to that.

The plan was, initially, accepted by both sides, but then ultimately tanked by Congress when Nehru voiced his opposition to the compulsory grouping of provinces, Jinnah’s key demand.

Drawing the line

Though the Cabinet Mission failed, Britain never lost sight of its goal: to get out of India as soon as possible.

In February 1947 Atlee appointed the last viceroy of British India, Lord Mountbatten, and instructed him to withdraw from India by June 1948.

Mountbatten brought forward the date of departure to August 1947 and officially announced the Partition Plan on June 2nd 1947. Despite continuously arguing for Indian unity, Congress accepted partition in order to banish the Muslim League to the into the north-east and north-west corners of the subcontinent, whilst retaining strong control at the centre. In other words, to be free of the League, partition was a price Congress was willing to pay.

Seeing no alternative and August 1947 fast approaching, Jinnah was forced to accept a “maimed, mutilated and moth eaten” Pakistan, an outcome he rejected vociferously in 1944 and again in 1946.

The modern nation states of Pakistan and India were born on August 14th and 15th respectively. The borders between the two, drawn up in a mere six weeks by a British lawyer who had no knowledge of India, were not revealed until at least two days after this.

Mountbatten congratulated himself for accomplishing one of “the greatest administrative operations in history”. He conveniently overlooked the almost unspeakable horror that accompanied his fast track partition.

Mountbatten congratulated himself for accomplishing one of “the greatest administrative operations in history”. He conveniently overlooked the almost unspeakable horror that accompanied his fast track partition.

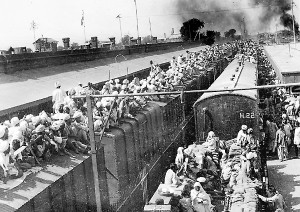

The country descended into a sort of civil war characterised by an animosity that is hard to overstate. Trains would leave packed with thousands of people forced to leave their homes, but would arrive filled with corpses riddled with bullet holes. Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs murdered and pillaged one another without a second thought, often aided by the state authorities.

Women were particularly targeted, raped, mutilated, abducted with nationalistic slogans etched and carved into their bodies to show the dominance of one group over another. To avoid such humiliation, many women committed mass suicide by jumping into wells or by being beheaded.

India and Pakistan had become independent and sovereign countries, born to the screams of 17 million refugees, and baptised in the blood of one million dead.